Non-Operational Words

I’ve talked previously about being a hardcore empiricist. I realized recently this makes me difficult to have a normal conversation with. My friend Raied put it best:

Mitchell, why don’t you ever answer my questions directly?

Instead, you ask me something like, “what do you mean by ‘mean’?”

It’s very frustrating.

Apparently I don’t do well with ambiguity. More specifically, I have a pet peeve regarding non-operational words. A non-operational word is simply a word that doesn’t have an operational definition. From wikipedia:

Operationalization is a process of defining the measurement of a phenomenon that is not directly measurable, though its existence is inferred by other phenomena. Operationalization thus defines a fuzzy concept so as to make it clearly distinguishable, measurable, and understandable by empirical observation.

I like calling things “non-operational” because it has a dual meaning. One is above. The other means the word just “doesn’t work” for me. It’s non-functional. To relate to the previous discussion, non-operational words are “purely abstract” and live in the abstract plane. I don’t know how to instantiate them in the real world.

Some people might call me pedantic. That might be true, depending on their definition of pedantic. But I claim that operationalizing isn’t just about science and engineering. It’s about getting on the same page with whoever you’re talking to. It’s about diving deeper into their mind to figure out what they really mean when they say they “want the world to be a better place.”

If you don’t operationalize effectively, you’re bound to have some miscommunications along the way. Below are a few examples.

Name That Color

Two of my lab mates (I’ll call them Doug and Evan) had a disagreement about the color of Evan’s glasses. Everyone agreed that Evan’s glasses frames looked BLACK.

But then Doug made an observation: if you held the frame up to the light, you could see the material was actually a deep, translucent red. And so Doug claimed the glasses were RED. Evan countered that it was a special case, and since they looked BLACK most of the time, the glasses were BLACK. Doug said the material was actually RED, so the glasses should be called RED regardless of how it appeared most of the time. And thus they were gridlocked.

Meanwhile, I’m in the back just begging for this stuff to be operationalized. Let’s start with grade-school physics, to get on the same page.

Source - DKFindOut!

Objects appear to have color because they only reflect certain wavelengths of light. White objects reflect most wavelengths, red1 objects reflect red light and absorb the rest, black objects absorb all the light. Interestingly, if you only have red lights in a room, everything looks either red or black, because there’s no other wavelengths to reflect.

So we might operationalize the definition of color as “the wavelength of light that bounces off or through the object and hits your retina when in the presence of white light.” That’s not bad, and it lets everyone be right. Depending on the experimental set-up, an object might be BLACK or RED at different times. It also makes clear the dependence of color on light available in the room and the position of the observer with respect to the object.

But why did Doug see RED? Some objects, while they don’t reflect light, allow certain wavelengths to pass through them. This has to do with the scattering effect of some translucent objects, and it’s why the sky is blue.

Source - EnchantedLearning

Of course, I explained that what Doug wanted to say might be more commonly understood as the refractive index of the material or something like that. But nope, Doug wouldn’t budge. The glasses were RED, that was that. Well, at least I tried.

Creative Sauce

Another day, my friend Ned told me he’d like to create a world in which “people express their maximum creativity.” Me being me, I asked him, “what do you mean by creativity?” His first definition wasn’t very satisfying:

People have some kind of “creative sauce” in their brains. I don’t know if it really exists, but you can tell when it comes out.

The first Google Images result for "art" - Source

I countered with an operational (if not very efficient) definition: I’d keep him with me wheverever I went. When I saw something I thought might be creative, I’d point to it, and he’d tell me whether or not it was actually creative. This is highly reproducible for me; there’s little ambiguity about what is and isn’t creative. It also makes it clear that the definition of creative is highly subjective.2 He didn’t really want to walk around with me, so he tried again:

A person is being creative when they observe something in the world and react to it.

I asked him if walking down the street was creative. After all, I’m observing the street and reacting to it. Obviously that’s not quite right, so he tried a third time:

Creativity is maximized when there’s high variance among the thoughts and actions of people in the world.

I finally got to the bottom of it. In his mind, the worst case scenario was something like 1984, where no one thinks independently and just accepts what the AI overlords tell them to think.

Now you might not think that matters much. But this all came up in the context of him deciding what job offer to accept and what he was going to do with his life. And if “maximizing creativity” is your life’s goal, you better know what it means. This brings me to…

Objections to Operationalizing

You don’t have to operationalize to come to a consensus.

Sure, sometimes. Spoon, chair, eat, person. People will understand what these things mean without defining them in terms of basic senses or empirical observations. The point of talking is to communicate information. If you reasonably believe that the person has a similar world view to you, and you can get away with just a few words, then by all means do so. Then you can both have a unified view of the world and how you’re going to build things moving forward.

But I’d argue misunderstandings are probably more common than people think. Consider “person.” I said you didn’t need to operationalize, but is a fetus a person? If so, then getting an abortion is murder and illegal. If it’s not, then abortion is a woman’s right to take control of her own body. What about robot people, a la Westworld? If a robot is indistinguishable from a normal person, do they still deserve human rights? Could you make them slaves?

Source - Vox

See, in order for the law to be effective, we need operational definitions of words. We need everyone to be on the same page, so we know what’s Gucci and what’s not. The abortion issue is centered around this: trying to operationalize when a fetus becomes a human. I’m not saying operationalizing will fix this problem; indeed it is the problem. But you can see how it’s necessary to gain concensus about what ought to be done.3

I don’t know enough about X to operationalize my words.

Great! Say that. We can look it up together. Or better yet, we can run some experiments and write a paper. If you really can’t operationalize something, it’s probably not productive to keep discussing it until we have more information.

Operationalization is impossible for some words.

Like I explained in my previous blog post, allowing things to live in the “abstract plane” is really just an un-scientific way of thinking and leads to these kinds of disagreements. You can’t apply reason to abstract things, because they exist outside of our single, unified model of the physical world.

And besides, because you are a human, you think in terms of sight, smell, taste, feel etc. Eventually everything can be reduced to some combinations of these feelings. Example: imagine a “kind” person. You now probably have some image in your head. Try to sharpen it. Are they smiling? What’s their body language like? What action are they in the middle of doing? How do they react to bullying? Etc. Operationalizing “kind” would be hard, but not impossible. These kinds of questions get you to the heart of what you actually mean when you say things (and may make you realize you didn’t mean what you said). This striving to define things in terms of empirical observations is a cornerstone of science.

Strangely, "kind person" on Google Images gets a lot of young people talking to old people - Source

In fact, non-operational words might also just be called “pre-scientific” words. Like Geoff Hinton mentioned in his Wired interview:

So 100 years ago, if you asked people what life is, they would have said, “Well, living things have vital force, and when they die, the vital force goes away. And that’s the difference between being alive and being dead, whether you’ve got vital force or not.” And now we don’t have vital force, we just think it’s a prescientific concept. And once you understand some biochemistry and molecular biology, you don’t need vital force anymore, you understand how it actually works.

I think that as we understand intelligence and neuroscience more, many words like “creativity” or “consciousness” will be recognized as prescientific terms just like “vital force” was. In general, the more science we do, the better we get at operationalizing things.

Abstractness

You might have some intuition about how hard it is to operationalize a word. You might say that a word is more “abstract” or “concrete” without being able to quite put your finger on what that means.

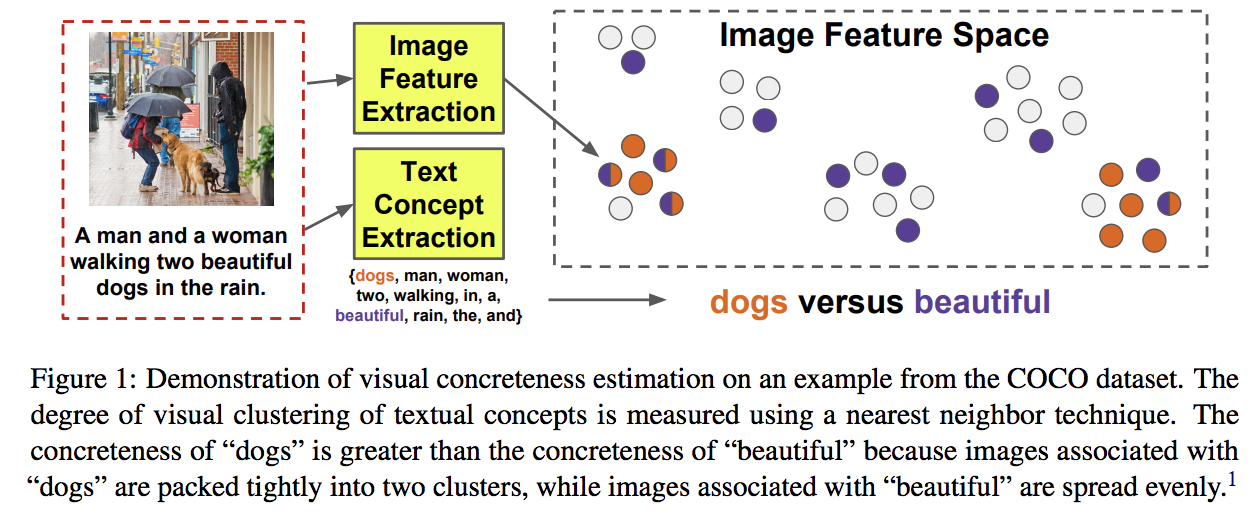

One of my favorite papers from last year operationalizes this idea of abstractness, provided you have a specific machine learning dataset with both pictures and words. In these datasets, each picture is tagged with some words (like on Flickr).

They define “abstractness” by how tightly images that your word describes are clustered in feature space. That’s kind of a heavy definition, so maybe think of it this way: all pictures tagged with “dog” have a dog in them somewhere. Those pictures are thus similar and clustered in feature space. “Dog” is concrete. However, “beautiful” is tagged on a bunch of pictures with extremely high variance. If one picture is tagged as “beautiful,” it’s not clear that it’s nearest neighbors will be tagged “beautiful” (not all pictures of the ocean are pretty). And therefore “beautiful” is abstract.

So even things that seem really hard to wrap your head around can be operationalized. Now, this might not be the best way to do it… but we can always certainly go back and revise our definition. At least we’re on the same page and can work towards that better definition. Actually, I really like this definition because it makes it clear that “abstractness” depends on the way in which you ground your concepts in physical senses (like sight). It’s dataset dependent.

Conclusion

So please, do me a favor: think deeply. Operationalize when you can. It’ll make your conversations more meaningful and help you avoid miscommunication. It’s one step closer to everyone getting on the same page.

- Mitchell

-

Defining which wavelengths are red isn’t quite so cut-and-dry. Depending on your language and whether you’re color blind, we might have a hard time agreeing on what to call red. But at the very least we can use a machine to measure the wavelengths of the light coming off the object. ↩

-

If we wanted to make it less subjective, we might imagine (theoretically) showing that potentially creative thing to everyone who spoke English and asking them to vote on whether or not it was creative. If more than half say yes, we could call it creative. If we actually ran this experiment, we might see some interesting results: maybe people tend to call things creative that are simply surprising? Then we could come up with a quantitative measure of surprising based on what usually appears on public television, social media, etc. Then we could short-cut the vote and make a prediction. Now that’s science. ↩

-

Apparently this is a favorite technique of Ben Shapiro while debating. Forcing a debate partner to get precise and specific about definitions can obliterate generalized arguments that aren’t grounded in reality. ↩