Does Pre-training Loss Linearly Predict Downstream Accuracy?

Since BERT was introduced, many improvements on the pre-training paradigm have been proposed to further boost performance, from using intermediate tasks1 to changing the pre-training objective.2 3 But why do these improvements work? Can we predict when learning to solve Task A will improve performance on Task B?

This post is about a very small piece of the transfer learning puzzle. I’ve noticed that when doing transfer learning in a few different circumstances, the pre-training loss/accuracy almost linearly predicts the downstream loss/accuracy. I don’t have a good explanation for it, but it suggests something “simple” is going on that we might exploit to further improve the pre-training paradigm. Here are a few examples.

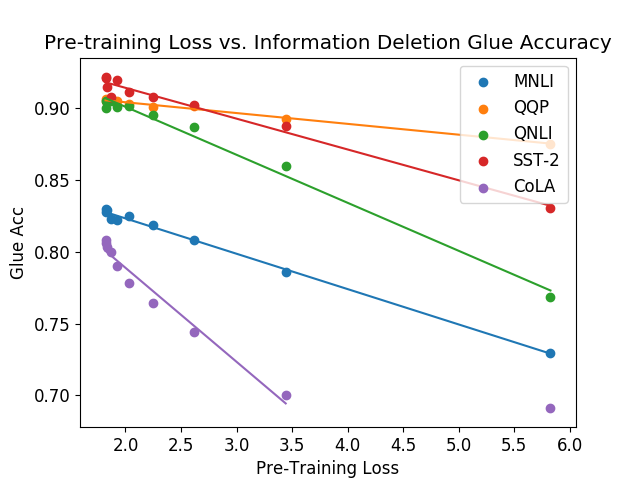

Pruning BERT

The first time I encountered this was when I was experimenting with pruning BERT.4

Each dot represents a version of BERT which has had some percentage of its weights deleted, forcing it to perform worse on the “masked language modeling” task. The pre-training loss achieved by each model is plotted on the x-axis, and the performance of each model on various GLUE tasks5 is plotted on the y-axis. I was surprised by how linear the relationship was.

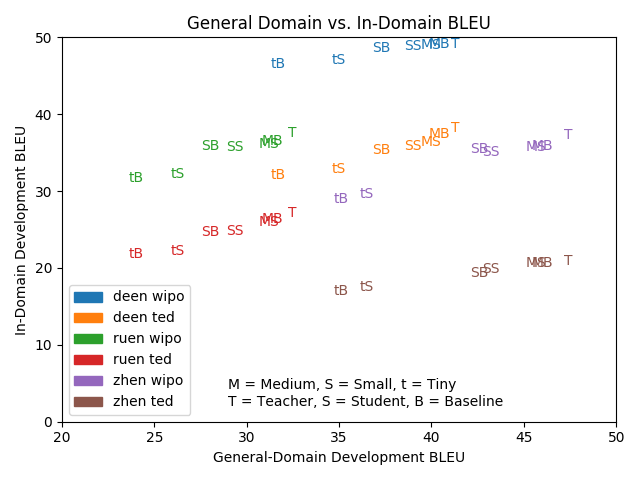

Domain Adaptation in MT

The second time I encountered this was during my experiments combining domain adaptation with knowledge distillation in neural machine translation.6 I wanted to know whether knowledge distillation impacted how easy it was to transfer an MT model from one domain to another.

Turns out, knowledge distillation doesn’t really interact with domain adaptation. The pre-trained BLEU score of an MT model (x-axis) linearly predicts the downstream BLEU score (y-axis). This is regardless of whether or not knowledge distillation was applied. Interestingly, the slopes in this case all seem to be pretty similar.

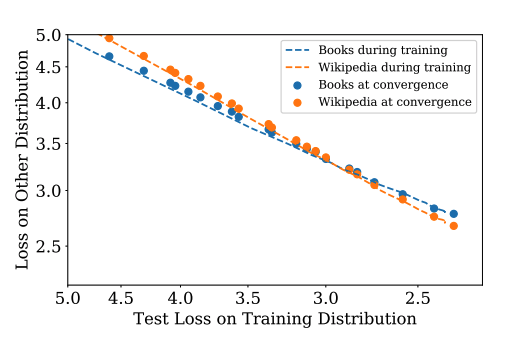

GPT Scaling Laws

Finally, when I mentioned this trend to Jared Kaplan, he said he’d also seen it in his work.

In his paper on scaling laws for language models7, they trained a bunch of language models and observed a power-law relationship between model size, dataset size, and language modeling loss. In that process, they noticed that language modeling loss on WebText was linearly related to language modeling loss on other datasets like Wikipedia and BookCorpus.8

Some Questions

Is this phenomenon robust?

It seems like this trend is pretty common, but obviously it has to depend at least somewhat on the training details, such as hyper-parameter selection. I’d like to know if and when this trend breaks down for certain tasks or models.

I’d also like to see some examples of negative slopes, such as the negative transfer documented in BERT on STILTS.1

Can we predict the slope?

A linear relationship seems to imply something “simple” is going on under the hood. But what is it? Do we understand this relationship well enough to predict when pre-training on one task will improve performance on a second task? Here’s a couple conjectures.

Dataset Size The simplest explanation is that the slope of the line is entirely predicted by how much data is present in the pre-training and the downstream datasets. However, recent empirical results makes me think dataset size is not a good predictor of task compatibility.9

Skills Instead, perhaps each task requires a certain set of “skills,” which are present in varying proportions in each dataset/task pair. A naive set of skills might be the set of tasks used for linguistic probing, although I suspect it’s much more complicated than that.10

This idea is supported by the fact that some kinds of pre-training hurt downstream performance if the tasks don’t align well.11 9 BART2 and MARGE3 also show that changing your pre-training objective to look more like your downstream task can help, supposedly because the “skills” required to do the new objective are more similar to the skills required to do the task.12 The MT and LM examples above also seem to indicate training on the same task with different data distributions usually helps.

Data Distribution Another predictor might be the how well the data distributions of the two tasks line up. For example, classification on movie subtitles might not transfer very well to classification of patent documents, since the sentences in one domain are pretty dissimilar to sentences in the other.

Can we manipulate the slope?

Once we can predict the slope, the next step would be to manipulate it. An interesting direction already underway is to procure domain or task-specific pre-training data to improve certain task performance.13 Another might be to do task-specific pre-training by filtering out certain kinds of pre-training data. This would make pre-trainined models much smaller.

Which tasks have the worst slopes?

A task with a very flat slope would imply that it won’t be “solved” by pre-training unless we follow the scaling curves impractically far to the right. What kind of task is that? Can we get better pre-training data for it?

When are two tasks compatible?

I think at the end of the day, the question in all of these domains (LM pre-training, MT domain adaptation, multi-lingual training, etc.) boils down to one simple question: when does training on Task A improve performance on Task B? It would be nice to have a framework for thinking about this. If anyone is aware of one, please let me know.

-

Phang, Jason, Thibault Févry, and Samuel R. Bowman. 2018. “Sentence Encoders on STILTs: Supplementary Training on Intermediate Labeled-Data Tasks.” arXiv [cs.CL]. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/1811.01088. ↩ ↩2

-

Lewis, Mike, Yinhan Liu, Naman Goyal, Marjan Ghazvininejad, Abdelrahman Mohamed, Omer Levy, Ves Stoyanov, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 2019. “BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-Training for Natural Language Generation, Translation, and Comprehension.” arXiv [cs.CL]. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/1910.13461. ↩ ↩2

-

Lewis, Mike, Marjan Ghazvininejad, Gargi Ghosh, Armen Aghajanyan, Sida Wang, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 2020. “Pre-Training via Paraphrasing.” arXiv [cs.CL]. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2006.15020. ↩ ↩2

-

Compressing BERT: Studying the Effects of Weight Pruning on Transfer Learning

Mitchell A. Gordon, Kevin Duh, and Nicholas Andrews

in Proceedings of the 5th Workshop on Representation Learning for NLP, ACL 2020. ↩ -

Wang, Alex, Amanpreet Singh, Julian Michael, Felix Hill, Omer Levy, and Samuel R. Bowman. 2018. “GLUE: A Multi-Task Benchmark and Analysis Platform for Natural Language Understanding.” arXiv [cs.CL]. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/1804.07461. ↩

-

Distill, Adapt, Distill: Training Small, In-Domain Models for Neural Machine Translation

Mitchell A. Gordon and Kevin Duh

in Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Neural Generation and Translation, ACL 2020. ↩ -

Kaplan, Jared, Sam McCandlish, Tom Henighan, Tom B. Brown, Benjamin Chess, Rewon Child, Scott Gray, Alec Radford, Jeffrey Wu, and Dario Amodei. 2020. “Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models.” arXiv [cs.LG]. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2001.08361. ↩

-

Jared also mentioned similar trends were noted in Appendix H of the GPT-3 paper. I didn’t include those because they plot model size on the x-axis instead of pre-training loss, although the implied relationship should be the same. ↩

-

Vu, Tu, Tong Wang, Tsendsuren Munkhdalai, Alessandro Sordoni, Adam Trischler, Andrew Mattarella-Micke, Subhransu Maji, and Mohit Iyyer. 2020. “Exploring and Predicting Transferability across NLP Tasks.” arXiv [cs.CL]. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2005.00770. ↩ ↩2

-

Petar Veličković has some interesting and similar thoughts on using graph algorithms for meta-learning. ↩

-

Pruksachatkun, Yada, Jason Phang, Haokun Liu, Phu Mon Htut, Xiaoyi Zhang, Richard Yuanzhe Pang, Clara Vania, Katharina Kann, and Samuel R. Bowman. 2020. “Intermediate-Task Transfer Learning with Pretrained Models for Natural Language Understanding: When and Why Does It Work?” arXiv [cs.CL]. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2005.00628. ↩

-

It’s unclear, however, how the “skills” required are determined by the task definition versus the data distribution. You can imagine language modeling on a children’s picture book requires vastly different skills than modeling Shakespear. While the “skills” hypothesis might be true, it’s not clear that it’s possible to use it to make falsifiable predictions. ↩

-

Beltagy, Iz, Kyle Lo, and Arman Cohan. 2019. “SciBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Scientific Text.” arXiv [cs.CL]. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/1903.10676. ↩