Ph.D. vs. Industry Work Dynamics

When I started my Ph.D., I struggled with the power dynamic between me, my advisor, and any collaborators I had, which was very different from my time in industry. This post is about some of those differences.

Industry

In the corporate world, there’s really only one solid rule: you do what your immediate supervisor wants you to do.1 The morality of this is debatable, but that’s usually just the way it goes. Boss says jump, you ask how high.2

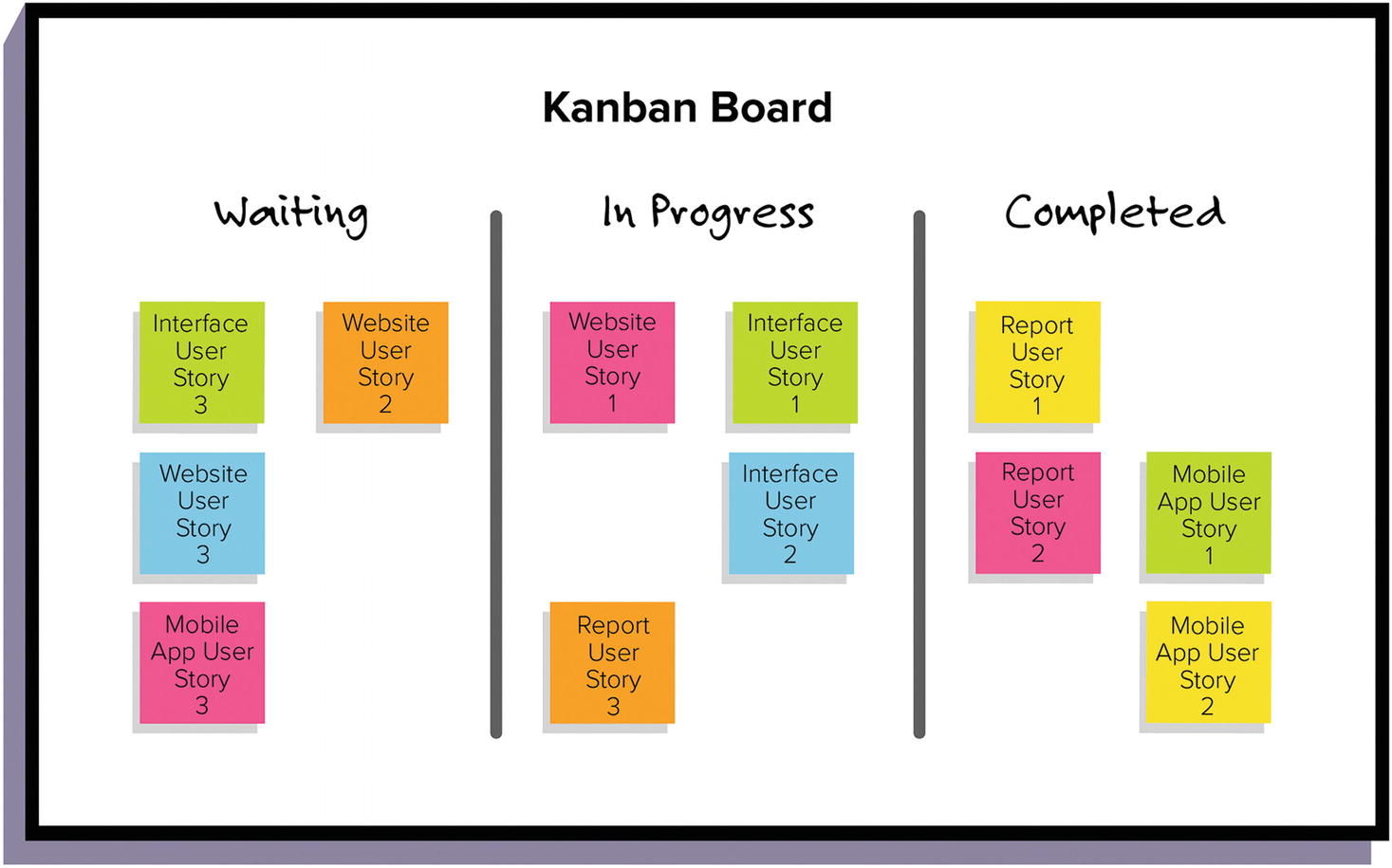

On software teams that translates into being a “team player.” The project manager sets goals, then sub-tasks are parceled out to different team members to reach those goals. You don’t have to think too hard about the long-term vision of the company; you just work the next ticket on the Kanban board. Do that, and everybody stays happy.

As you move up the management ranks, the scope of your responsibilities expands, but it’s still usually clear what those responsibilities are. They just get more vague as you move up the ladder. As you climb the ladder, you go from “implementing features” to “build a thing that does X” to “increasing revenue in X facet of our business” or “increasing user engagement.”

Boss-employee relationships reflect a weird kind of feudal loyalty. It’s an exchange of trust. You display loyalty to your immediate supervisor, and in return they protect you from forces elsewhere in the company. This dynamic can feel reassuring to some and stifling to others.

Academia

Academia is much less hierarchical. Projects in academia feel more like temporary federations of independent entities, with loose ties mainly dictated by who’s getting funding from where. This is an important difference: as a Ph.D. student, you don’t have a boss.

On one hand, this means you have more intellectual freedom. You can spend your time as you see fit; you don’t have to clock in or out of a Ph.D., which can be a boon to your intellectual development. But this freedom comes with increased responsibility. Specifically, you’re responsible for three things: staying funded, succeeding at research, and finishing your thesis.

Staying Funded

Your intellectual freedom means it’s your responsibility to stay funded. You can get a fellowship (if possible) or get funding from your advisor. You won’t get fired if your advisor isn’t happy with you, but they can choose to stop paying you.3 Depending on your advisor’s temperament, this can be easy or difficult.

If your advisor is very hands-off, they might be ok with you doing your own thing. Professors with tenure are more likely to be like this, since they’re more secure in their position. Some advisors, though, really need cheap labor. Just as you’re responsible for getting funding for yourself, your advisor is responsible for getting funding for their lab. In the worst case, your advisor might try to dictate your every move. But more often, you have to work on a “grant project” once a year that satisfies your advisor’s grant proposal.4

Research Success

But while you need to stay funded, you are also responsible for your own research success. This includes choosing to work on the right projects and making sure they succeed. Depending on your situation, there can be some tension between staying funded and succeeding at your research.

Your collaborators and advisor will often suggest projects or experiments within projects (see above). Doing those things may earn you brownie points, but it comes with none of the benefits of “following orders” in the industry world. You can’t blame them when things go wrong, and they can’t offer you any protection against failure. If your projects fail, then you won’t graduate. Simple facts.

So it’s very important to learn how to say “no,” without burning any bridges. Sometimes you should follow advice, and sometimes you should recognize that their suggestion is really just that, a suggestion. As the Ph.D. progresses, it’s very common for advisors to not be tuned in to the sub-field as well as their student, who has had “feet on the ground” in the area much more recently.

This also means that your relationship with collaborators is very different in academia vs. industry. In industry, everyone takes orders from the boss, and so teamwork is usually a function of how well your boss is doing their job and the company culture.

In academia, it’s much more fluid. People can say they’ll help but then drop off the map after a month. Or collaborators will want to help, but then be uninformed about the field you’re trying to publish in and not understand what’s going on. The most successful setup I’ve seen is when there are one or two “lead authors” who are the “captains” of the project. They maintain the vision for the project and then parcel out sub-tasks to collaborators depending on their abilities or motivations. It’s interesting how much this sounds like being a project manager in industry, without any of the formal leadership titles.

So part of my Ph.D. journey has really been about owning my work, gaining the skills required to make long-term research proposals, and figuring out how to frame and pitch projects to different scientific communities and collaborators. It’s harder than just “working on the next Kanban ticket,” but I think it will be more rewarding in the end.

Finishing Your Thesis

If you’ve made it through the first two points then your only barrier to finishing is writing and defending your thesis. To do this, you need the approval of three people who compose your thesis committee. This is why it’s important to not burn bridges. Your advisor and collaborators will eventually determine whether you can graduate.

All in all, I think the Ph.D. process is a delicate dance between operating within the system and being an independent thinker. It’s engineered to produce researchers who can stand on their own two feet and fend for themselves. So you can’t just do everything your advisor tells you to do (as you might in industry) but you also can’t ignore them completely, because they play an important role in completing your Ph.D. and ideally in mentoring you to become that ideal researcher.

The fuzziness of the student-advisor relationship can lead to a lot of dysfunction, and so if you’re thinking about starting a Ph.D. it’s important to get on the same page with your advisor early on.

-

My dad always used to say this when I was a kid. He was the president of his company. ↩

-

If your advisor is really unhappy, they can make a case to have you removed from the program. But in most cases they can’t make that decision on their own and need to go through some formal processes. ↩

-

There are a wide range of advisor types. ↩